Noir has a long tradition on the roadways. Ida Lupino’s classic The Hitch-Hiker taught us that picking up hitchhikers can get you killed. The 1986 pseudo-remake also The Hitcher told us that worse than getting you killed picking up hitchhikers can make you wish you had been killed. Steven Spielberg’s directorial debut Duel (not really noir) warned us about road rage. The Noirish thriller Joyride told us not to mess with truckers. Today I am promoting two of the best noirs to involve crime on the road. They both involve a highway and a death (or two) and lots and lots of nasty human behaviour. Each film is a classic in its own way. Detour may be the greatest Hollywood “B” movie ever made. It has minimal plot, less sets, and performances to die for. On the other end of the spectrum is Muerte de un Ciclista (Death of a Cyclist). It is a classy Spanish movie made with all the financial trimmings you expect from a A level production. The two movies could not be more different nor could they be more exceptional.

Subscribe to never miss a post!

Muerte de un Ciclista (Death of a Cyclist)

🦛🦛🦛🦛

Noir movies conjure images of foggy streets, fedoras, smoking, sexpot dames, and 1940s Hollywood, but noir can come from other decades and all around the world, as this Spanish masterpiece from 1955 proves. Writer/director Juan Antonio Bardem has here seemlessly tied two movies into one: a brilliant noir and a searing social commentary. The noir is front and centre, the social commentary is more subtle and best viewed through the lens of history. The opening scene shows a lonely street and a solitary cyclist. A racing car and squealing brakes come next. We only see the after effects of the crash, a subtlety that reminds us how effective unseen violence can be at conveying tragedy. The cyclist is not dead, but the couple in the car leave him to die because they are having an affair and keeping their secret is worth more to them than the life ebbing out on the side of the road. It is classic noir material, but how Juan and Maria José’s secret affair leads to a callous disregard for human life fuels the social commentary. It is a masterpiece of an opening sequence. There are more brilliant sequences to come as the ill-fated lovers navigate what comes next. Themes of guilt and lovers pulled in different directions but irrevocably tied together by their crime are movie staples. Part of what makes this script special is that what comes next does not include a detective or any kind of search for justice. The crime is not investigated; instead, the consciences of the two protagonists are what’s on trial. There is a distinctly foreign flavour that goes beyond subtitles in this movie. It is also subtle, unlike many Hollywood noirs, which were often blunt. The wonderful performances are also full of subtlety. Alberto Closas plays Juan as a man gradually succumbing to increasing feelings of guilt over leaving a person to die. His lover Maria José has an opposite response. As events unfold, we come to realize that Maria José is only conflicted about how much of herself she is willing to sacrifice to maintain the comfort she is accustomed to. Lucia Bosé doesn’t play Maria José as if she is surprised by her own moral debasement, but rather as a person committed to convincing themself that it is okay. The third major player is Maria José’s cuckold husband Miguel (Otello Toso), who may be a lot more aware than he gets credit for. I loved how much ambiguity Toso brings to his performance, what Miguel knows and how he will deal with any knowledge he has becomes a central question. I was fascinated by how Bardem intertwined the cover-up of the affair and the murder through the eyes of his protagonists. It slowly dawned on me that they did not view things through the same value system lens that Bardem intended the audience to see through. Bardem avoids standing in conventional judgment of the characters. The lens he wants the audience to see through, and what he wants the audience to join him in condemning Juan and Maria for, is their elitist, bourgeois, fascist worldview. Fascist is the keyword because this movie was made in Fascist Spain under the Sauron-like gaze of Dictator Franco. Using the medium of noir is not just good filmmaking; it is a means to conceal the film’s criticism of the system in which the director lived and made the movie. It is not always subtle, and it is surprising that some of it got past the censors. Sadly, the intended masterstroke of social commentary ending did not make it past the censors. I won’t discuss that here, as it would give away the ending. Sufficient to say that the revised ending is still a brilliant noir ending. That’s how good this movie is. They gutted the ending, and it is still great. I don’t know anyone else but the incomparable Orson Welles, who managed that, with The Magnificent Ambersons. Great noir requires great visuals, and Bradem and his crew provide them in spades. Shot beautifully in black and white, this movie has all the glamour B&W can bring and all the shadows you could wish for. My favourite scene is where Bardem lets the soundtrack drown out the hushed conversations taking place between the major players at a party. The camera wanders around watching each of them observe each other’s conversations, and leaves them and the viewers to speculate about what is being said. Divine. Music, like cinematography, is a significant mood enhancer. It is used to great effect in a scene where potential blackmailer “Rafa” (Carlos Casaravilla in a scene-stealing performance) taunts Juan and Maria José in front of her husband with what he may or may not know. The intermittent sound of tinny piano playing effectively grates on the nerves. It is as effective a use of music as I have enjoyed in a movie. A timeless and universal moral tale makes this a brilliant example of noir. Knowing the movie’s origins made me appreciate it more. The tightrope Bradem so skillfully walked to make a movie criticizing fascism under fascist eyes is possibly even more impressive. This movie serves as a poignant reminder that knowledge about a film can significantly enhance one’s understanding of and appreciation for it. The very best movies are entertaining, but not just entertaining.

Where to watch

Streaming on The Criterion Channel. Rent from the usual suspects: Amazon, Apple, and YouTube.

Thoughts? Feel free to weigh in!

Detour (1945)

🦛🦛🦛🦛

To love classic film noir is to love Detour and if you haven’t seen it yet, you are in for a treat. Made by Producers Releasing Corporation, one of the so-called “Poverty Row” studios, Detour, on the face of things, has next to nothing going for it. It has no big stars, no famous director, unremarkable source material, and it was made on a shoestring budget. So shoestring that the nicest set/prop is a car that reportedly belonged to director Edgar G. Ulmer. What makes Detour so great might actually stem from its low budget and lack of flashy elements. There are definitely “better” noir films, such as Out of the Past (1947) and Kiss Me Deadly (1955), to name a couple, but even those masterpieces can only match Detour for being pure noir at heart. Detour is about how one man’s life is completely ruined by a series of random circumstances and terrible choices in a relentlessly descending spiral of despair. The movie takes place as Al Roberts (Tom Neal) travels cross-country from New York to Los Angeles. The film barely clocks in at over an hour, so there is no fat on this one. Al is living in N.Y. and missing the love of his life, who has moved to LA. so, he decides to hitchhike cross country to join her. He gets picked up by Charles Haskell Jr. (Edmund MacDonald), a friendly enough guy. It turns out to be the worst mistake of Al’s life, or it would have been except that a little bit later, Al, now driving Mr. Haskells’ car, picks up fellow hitchhiker Vera (Ann Savage), and with that, the wheels officially come off the proverbial car. It would be a crime to give away more, but rest assured that what comes next is at times jaw-droppingly shocking. Director Ulmer and screenwriter Martin Goldsmith are surely due some credit for how tight this movie is. Though, reportedly, the studio editing process significantly cut down what was actually shot. The real stars of this movie are leads Tom Neal and Anne Savage. Neal, who narrates the whole film, an inexpensive way of doing exposition, looks haggard and distraught from the first scene. You feel his pain, but more importantly, you feel his humanity and wince as he makes every possible wrong choice. Savage is even better, delivering an outstanding performance as a genuinely horrible person. I am a little surprised that her villainy slipped by the censors, but one of the perks of the “Poverty Row” studios seems to have been that they were scrutinized a little less closely than the big studios. Even if the rest of the movie had stunk, and it very easily could have, Savages’ performance would remain a must see. Detour has its flaws, but it is the noir to the core: unrelenting, unsympathetic and unapologetic in stating that sometimes life just sucks. It was so much fun to watch, I’m grinning just thinking about it.

Where to watch

Streaming on Amazon Prime, The Criterion Channel. Rent from the usual suspects: Amazon, Apple, and YouTube.

Please share this post with anyone who may enjoy it.

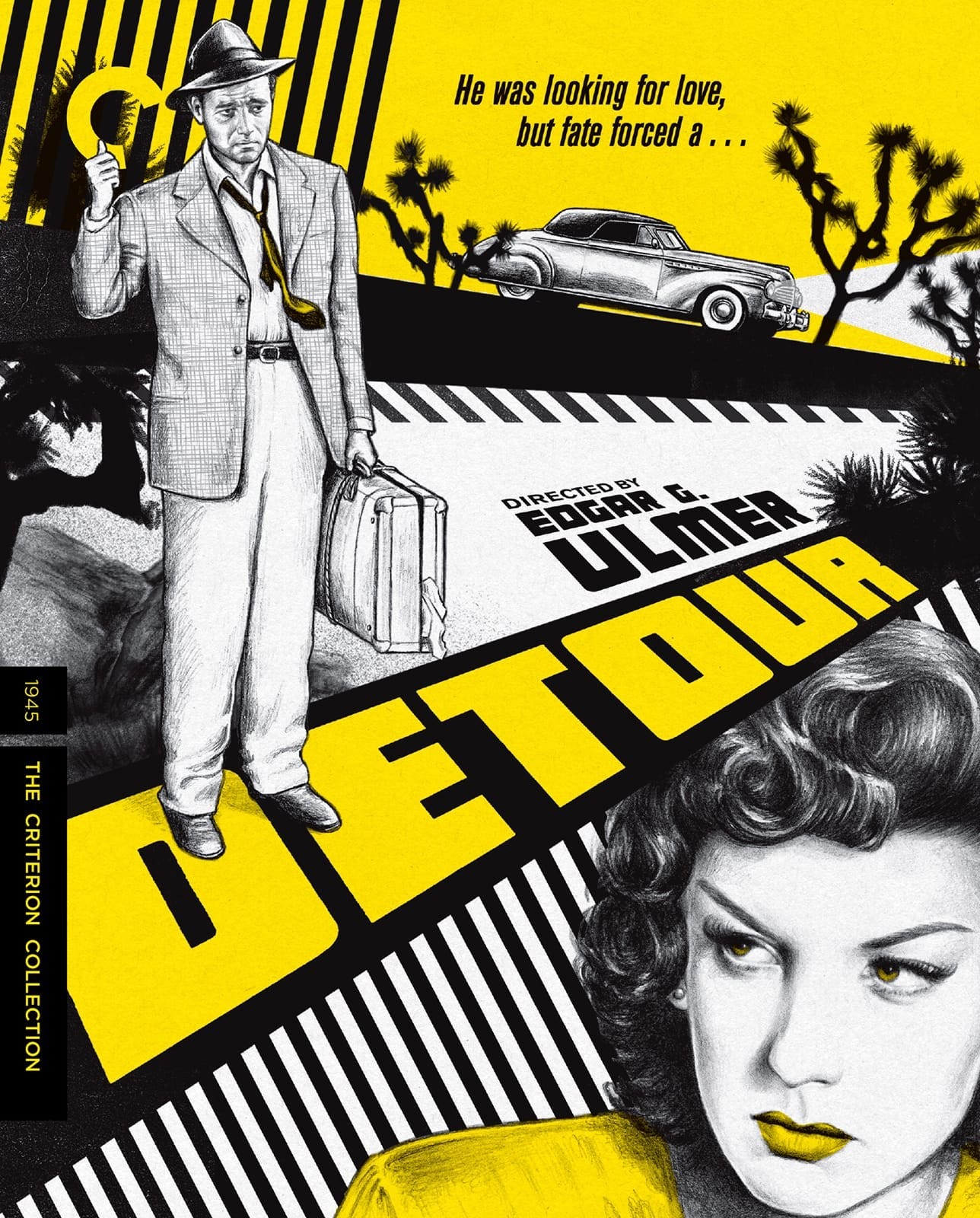

That’s a wrap and man does revisiting these two movies ever make me want to re-watch them both. Detour in particular with its short run time is one that is easy to sneak in sometime in Noirvember. I want to give a shout out to what may been my favorite Criterion Collection DVD cover. I never would have thought to put bright yellow on a noir cover but this brilliant cover (I suspect inspired by Frank Millers genius noir comic Sin City) does so perfectly and gives us an all time classic tag line to boot. Don’t foget to shout out your thought in the comments.